The HOSP Wars, Part I

HOUSE SPARROWS

House Sparrows are the most abundant songbirds in North America and the most widely distributed birds on the planet. House Sparrows are not actually sparrows, but are Old World Weaver Finches, a family of birds noted for their ingenious nest-building abilities.

HISTORY

House Sparrows were introduced into North America from England in the 1850s on the mistaken premise that they would help reduce crop insect pests. At first, the new immigrants welcomed this little bird of their homeland. Within 25 years, however, they realized the seriousness of their mistake: the House Sparrow population had increased at an explosive and alarming rate, and the birds were causing extensive damage to crops and fruit trees. They were also taking over the nesting sites of native cavity-nesting birds.

LIFE AND HABITS

The breeding season for House Sparrows begins early in the spring or even in midwinter, and each pair may produce up to four broods a season. The male House Sparrow's bond with his nest site is stronger than his bond with a mate he may lose a mate, but he won't give up his nest site. Although they usually prefer to nest in a cavity, House Sparrows will settle for any nook or cranny they can find. They will also occasionally nest in coniferous trees and in the nests of Cliff Swallows and Northern Orioles.

The male constructs a bulky, dome-shaped nest of coarse grasses, weeds, hair, and feathers. The female lays three to five white/brown speckled eggs and incubates for 11-14 days. The young sparrows fledge after 14-16 days. They are not migratory, but flocks of birds move about within a 1.5-2mi. area. House Sparrows are primarily seed-eaters, although they eat some insects during the summer. They will also dine on garbage. Feedlots and farmsteads are particularly attractive to sparrows as they provide an abundant source of food, as well as shelter and plenty of nesting sites.

-reprinted with permission from the North American Bluebird Society

House Sparrows are the most abundant songbirds in North America and the most widely distributed birds on the planet. House Sparrows are not actually sparrows, but are Old World Weaver Finches, a family of birds noted for their ingenious nest-building abilities.

HISTORY

House Sparrows were introduced into North America from England in the 1850s on the mistaken premise that they would help reduce crop insect pests. At first, the new immigrants welcomed this little bird of their homeland. Within 25 years, however, they realized the seriousness of their mistake: the House Sparrow population had increased at an explosive and alarming rate, and the birds were causing extensive damage to crops and fruit trees. They were also taking over the nesting sites of native cavity-nesting birds.

LIFE AND HABITS

The breeding season for House Sparrows begins early in the spring or even in midwinter, and each pair may produce up to four broods a season. The male House Sparrow's bond with his nest site is stronger than his bond with a mate he may lose a mate, but he won't give up his nest site. Although they usually prefer to nest in a cavity, House Sparrows will settle for any nook or cranny they can find. They will also occasionally nest in coniferous trees and in the nests of Cliff Swallows and Northern Orioles.

The male constructs a bulky, dome-shaped nest of coarse grasses, weeds, hair, and feathers. The female lays three to five white/brown speckled eggs and incubates for 11-14 days. The young sparrows fledge after 14-16 days. They are not migratory, but flocks of birds move about within a 1.5-2mi. area. House Sparrows are primarily seed-eaters, although they eat some insects during the summer. They will also dine on garbage. Feedlots and farmsteads are particularly attractive to sparrows as they provide an abundant source of food, as well as shelter and plenty of nesting sites.

-reprinted with permission from the North American Bluebird Society

The practice of pairing boxes for native cavity nesting birds is not a new one. Traditionally, boxes are spaced 12 to 15 feet apart to accommodate Eastern Bluebirds (EABL) and Tree Swallows (TRES). When the birds cooperate, this is a beautiful thing. They work in tandem to defend both nestboxes. If EABL are off the nest feeding, the TRES will sound the alarm and attack any nestbox intruders. EABL will do the same. Unfortunately, these two species do not always cooperate.

More aggressive, territorial EABL will oftentimes thwart a TRES attempt to inhabit the paired box and House Sparrows (HOSP) take it. Other times, TRES may inhabit a box and find themselves with HOSP neighbors. Nonnative, aggressive HOSP nesting this close to any desirable native cavity nester seems a risky proposition, but can be dealt with effectively.

When HOSP claim a paired box, one's first intuition may be to decry the paired box concept altogether, but you have to realize that HOSP will attempt to claim your nestboxes regardless of whether they are paired. If EABL or TRES occupy an isolated box without an empty one nearby, HOSP will attempt to usurp this box. In doing so, they often corner and kill the adult birds, their eggs and/or young. With an empty paired box next door, they are much more likely to try to use this one rather than expend the energy necessary to fight their native neighbor. I view a paired box as an added line of defense in the HOSP wars, but how you proceed once they are there is tricky. Your action or inaction can result in success or disaster.

What works?

The very best course of action, as soon as a HOSP is seen in or on a nestbox, is to trap him/her with an inbox trap. The Van Ert Universal Sparrow trap is a wonderful tool in the HOSP arsenal (other traps are the Huber and Gilbertson Universal). Trapped HOSP should be humanely dispatched and trap reset if you have seen evidence of mate near the nestbox. The male HOSP generally claims the nestbox, and you can sometimes trap him before he attracts a mate. As soon as the male is dispatched, trap is removed, nestbox is scraped clean and ready for a desirable native cavity nesting bird or for the next HOSP that "tries" to use it. This is the way I manage all my paired nestboxes on my trails and I have never had any problems with "retaliation". Once the HOSP is gone, the threat is gone.

If you cannot bring yourself to trap HOSP, another more risky method is to allow the HOSP to nest, but render their eggs nonviable. I did experiment with this method one season when I was new to Bluebirding. My favorite way of rendering eggs nonviable is to take half the clutch, mark those eggs with a permanent marker (so you know which ones are nonviable), and refrigerate them for at least 24 hours. Now remove the remainder of HOSP clutch and replace it with the nonviable eggs. Make sure to allow eggs to warm back up to room temperature or a little above so female does not realize they are cold when she sits on them. You can warm them in your hands. I imagine microwaving them on low would also work as long as you don't overdo it. Monitor the box weekly and remove any new, unmarked eggs, replacing them with your marked nonviable refrigerated ones as you like. I have had HOSP sit on a nest for a month before realizing clutch is nonviable. Of course, once they realize this, they will abandon the box and nest elsewhere, raising a successful brood that can cause you problems in the future.

There are other methods for rendering HOSP eggs nonviable. Although freezing eggs works, I do not recommend this because recently laid eggs with their high water content will crack when frozen. Shaking the eggs is unreliable. Piercing eggs with pin or finger lance is effective if you make sure the pin goes in to center and you pierce the yolk with it, but this method often results in egg contents leaking into nest and HOSP abandoning for more successful (box next door?) nesting site.

I have also heard of people having success replacing HOSP eggs with plastic craft eggs that look similar to theirs. Whether or not they will accept these or realize something is amiss, I cannot say for sure as I have never tried it myself. I have used plastic craft eggs as a trapping tool, however. HOSP will actually try to remove these from the nest if they have not started their clutch yet.

What doesn't work?

Pulling nests and/or eggs is a standard method of discouraging HOSP, but I do not recommend it. The theory is that removing the nest and eggs will drive them away from your nestboxes. This does happen in some instances, but for the most part, HOSP are extremely tenacious and will not abandon the box for quite some time, rebuilding their nest again and again. At some point, they will finally abandon the site, but will successfully nest somewhere near. They may return, along with their breeding age young, to your nestboxes next year.

My mentor, Darlene Sillick, and I conducted a limited experiment on a paired box trail one spring where we pulled HOSP nests and discontinued inbox trapping of HOSP. Nestboxes were checked every 7 days. For the first month or so, HOSP left their TRES or EABL neighbor alone. After about a month, HOSP stepped up their nesting timetable, building an entire nest and laying eggs in a week's time. Once we began removing nests AND eggs, they killed the adult TRES and young in the adjacent paired nestboxes. The term "retaliation" is often used to describe this behavior, but I believe as nesting season wore on, they saw their nestbox was unsuccessful and observed the adjacent bird's box was successful. Testosterone levels were soaring and aggressive response was inevitable. I will say that during field observations of HOSP/TRES interactions and HOSP/EABL interactions, EABL are much better at defending their lives and their nestboxes than TRES are. Their superior size and direct flight path makes them a formidable foe against a marauding HOSP.

Another common mistake is when people leave the HOSP alone in fear that they will "retaliate" or because they do not believe HOSP are a problem. This is the very worst course of action. It is very important that you NEVER let them raise a family, as the HOSP and their young will return the following nesting season to use your nestboxes. Allowing HOSP to propagate is a recipe for disaster as native cavity nesters will abandon your nestboxes for safer nesting sites.

If native cavity nesters are successful raising young in your nestboxes, they will return to nest with you brood after brood, season after season. If they are unsuccessful, they will not. The same rule applies for HOSP with the exception that new pairs will be an ongoing problem, even with trapping. However, with active HOSP control, you will see an impressive decrease in their numbers in a very short time.

More aggressive, territorial EABL will oftentimes thwart a TRES attempt to inhabit the paired box and House Sparrows (HOSP) take it. Other times, TRES may inhabit a box and find themselves with HOSP neighbors. Nonnative, aggressive HOSP nesting this close to any desirable native cavity nester seems a risky proposition, but can be dealt with effectively.

When HOSP claim a paired box, one's first intuition may be to decry the paired box concept altogether, but you have to realize that HOSP will attempt to claim your nestboxes regardless of whether they are paired. If EABL or TRES occupy an isolated box without an empty one nearby, HOSP will attempt to usurp this box. In doing so, they often corner and kill the adult birds, their eggs and/or young. With an empty paired box next door, they are much more likely to try to use this one rather than expend the energy necessary to fight their native neighbor. I view a paired box as an added line of defense in the HOSP wars, but how you proceed once they are there is tricky. Your action or inaction can result in success or disaster.

What works?

The very best course of action, as soon as a HOSP is seen in or on a nestbox, is to trap him/her with an inbox trap. The Van Ert Universal Sparrow trap is a wonderful tool in the HOSP arsenal (other traps are the Huber and Gilbertson Universal). Trapped HOSP should be humanely dispatched and trap reset if you have seen evidence of mate near the nestbox. The male HOSP generally claims the nestbox, and you can sometimes trap him before he attracts a mate. As soon as the male is dispatched, trap is removed, nestbox is scraped clean and ready for a desirable native cavity nesting bird or for the next HOSP that "tries" to use it. This is the way I manage all my paired nestboxes on my trails and I have never had any problems with "retaliation". Once the HOSP is gone, the threat is gone.

If you cannot bring yourself to trap HOSP, another more risky method is to allow the HOSP to nest, but render their eggs nonviable. I did experiment with this method one season when I was new to Bluebirding. My favorite way of rendering eggs nonviable is to take half the clutch, mark those eggs with a permanent marker (so you know which ones are nonviable), and refrigerate them for at least 24 hours. Now remove the remainder of HOSP clutch and replace it with the nonviable eggs. Make sure to allow eggs to warm back up to room temperature or a little above so female does not realize they are cold when she sits on them. You can warm them in your hands. I imagine microwaving them on low would also work as long as you don't overdo it. Monitor the box weekly and remove any new, unmarked eggs, replacing them with your marked nonviable refrigerated ones as you like. I have had HOSP sit on a nest for a month before realizing clutch is nonviable. Of course, once they realize this, they will abandon the box and nest elsewhere, raising a successful brood that can cause you problems in the future.

There are other methods for rendering HOSP eggs nonviable. Although freezing eggs works, I do not recommend this because recently laid eggs with their high water content will crack when frozen. Shaking the eggs is unreliable. Piercing eggs with pin or finger lance is effective if you make sure the pin goes in to center and you pierce the yolk with it, but this method often results in egg contents leaking into nest and HOSP abandoning for more successful (box next door?) nesting site.

I have also heard of people having success replacing HOSP eggs with plastic craft eggs that look similar to theirs. Whether or not they will accept these or realize something is amiss, I cannot say for sure as I have never tried it myself. I have used plastic craft eggs as a trapping tool, however. HOSP will actually try to remove these from the nest if they have not started their clutch yet.

What doesn't work?

Pulling nests and/or eggs is a standard method of discouraging HOSP, but I do not recommend it. The theory is that removing the nest and eggs will drive them away from your nestboxes. This does happen in some instances, but for the most part, HOSP are extremely tenacious and will not abandon the box for quite some time, rebuilding their nest again and again. At some point, they will finally abandon the site, but will successfully nest somewhere near. They may return, along with their breeding age young, to your nestboxes next year.

My mentor, Darlene Sillick, and I conducted a limited experiment on a paired box trail one spring where we pulled HOSP nests and discontinued inbox trapping of HOSP. Nestboxes were checked every 7 days. For the first month or so, HOSP left their TRES or EABL neighbor alone. After about a month, HOSP stepped up their nesting timetable, building an entire nest and laying eggs in a week's time. Once we began removing nests AND eggs, they killed the adult TRES and young in the adjacent paired nestboxes. The term "retaliation" is often used to describe this behavior, but I believe as nesting season wore on, they saw their nestbox was unsuccessful and observed the adjacent bird's box was successful. Testosterone levels were soaring and aggressive response was inevitable. I will say that during field observations of HOSP/TRES interactions and HOSP/EABL interactions, EABL are much better at defending their lives and their nestboxes than TRES are. Their superior size and direct flight path makes them a formidable foe against a marauding HOSP.

Another common mistake is when people leave the HOSP alone in fear that they will "retaliate" or because they do not believe HOSP are a problem. This is the very worst course of action. It is very important that you NEVER let them raise a family, as the HOSP and their young will return the following nesting season to use your nestboxes. Allowing HOSP to propagate is a recipe for disaster as native cavity nesters will abandon your nestboxes for safer nesting sites.

If native cavity nesters are successful raising young in your nestboxes, they will return to nest with you brood after brood, season after season. If they are unsuccessful, they will not. The same rule applies for HOSP with the exception that new pairs will be an ongoing problem, even with trapping. However, with active HOSP control, you will see an impressive decrease in their numbers in a very short time.

Pairing Boxes for

House Sparrow

Control

by Paula Ziebarth

House Sparrow

Control

by Paula Ziebarth

Male (top) and female House Sparrows have claimed a nestbox.

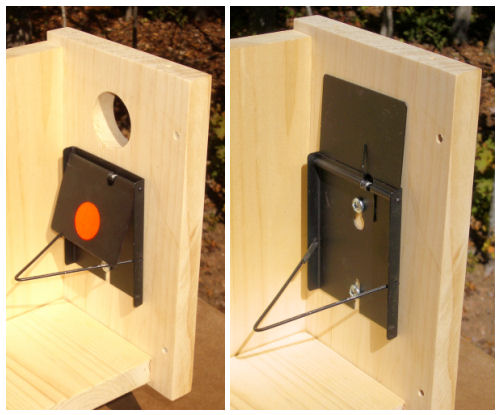

VanErt sparrow trap

At left is set position; right is tripped

At left is set position; right is tripped

Huber sparrow trap

At left is set position; right is tripped

At left is set position; right is tripped

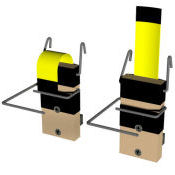

Gilbertson universal sparrow trap

At left is set position; right is tripped

At left is set position; right is tripped

Home | Site Map | Disclaimer | Contact Us

Copyright © 2012 NestboxBuilder.com

This site was last updated on 01/01/2016

Copyright © 2012 NestboxBuilder.com

This site was last updated on 01/01/2016

Links

Van Ert Sparrow traps available at

http://www.vanerttraps.com/

Plans for the Huber and Gilbertson sparrow traps are availble on our Plans Page.

For further reading and study

http://www.sialis.org/index.html

http://www.vanerttraps.com/

Plans for the Huber and Gilbertson sparrow traps are availble on our Plans Page.

For further reading and study

http://www.sialis.org/index.html